On November 20, a panel discussion of the results of the study “Image of the Future: Israel after the War“ was held in Tel Aviv. The study was developed by the Analytical Center of the NGO “Dor Moriah” (Haifa) and implemented with the support of the sociological center “Maagar Mochot” (Tel Aviv) from 12.11.2023 – 16.11.2023.

The research included interviews and surveys with a representative sample of the adult population of Israel (1004 people). The discussion on November 20th was attended by political scientists, rabbis, journalists, and specialists in information technology.

Mikhail Finkel – political scientist, rabbi; Yuval Peleg – media expert, political scientist, lobbyist; Daniel Gricero – political strategist, expert in working with political movements and the media

The acute problems for the future

Now, with an extensive ground operation in the Gaza Strip underway, it is evident that the defeat of HAMAS is only part of the problem. The justification for this intense operation largely depends on the decisions that will be made regarding the Gaza Strip and how the situation in this territory will develop. What Israelis think about this is the focus of the study “The Image of the Future: Israel after the War.”

Will there be, as Biden demands, a Gaza transfer under the control of Abu Mazen and the Palestinian Authority? Will the Gulf monarchies be involved in the reconstruction of Gaza? Will a Palestinian state be established, or will the resolution of the “Palestinian state” issue remain in its current format?

There are quite a few possible future scenarios, ranging from the complete annexation of Gaza, Judea, and Samaria to the creation of a Palestinian state within the borders outlined by UN resolutions.

What percentage of Israelis supports one scenario or another? This determines how intense the domestic Israeli public and political discussions will be regarding the ways to address the “Palestinian state” issue.

In 2023, the Analytical Center “Dor Moria” studied the attitudes of Israelis toward topics that divided Israeli society. Topics that sparked various forms of civil opposition: the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, judicial reform, Israel’s neutrality question, and expectations of Israelis from the U.S. presidential elections. Some of these issues led to heated discussions and mass protests for an extended period. Pre-war studies by our analytical center showed a deep divide in Israeli society on many issues (such as judicial reform or the Russo-Ukrainian conflict). Then, on October 7th, something happened, and society seemed to consolidate around a common disaster and a common war.

Roy Yankelovich – journalist «The time of Israel».

After overcoming the initial shock from October 7th and following a month of war between Israel and HAMAS, the topic of what will happen to Gaza and all of Israel after the destruction of Hamas is constantly discussed in everyday communication, in the press, and at the political level. The results of the survey “The Image of the Future: Israel after the War” reflect the absence of any mainstream consensus regarding the post-war future and division along political and ethno-confessional lines. This polarization, with a weak “center,” highlights the risks of increasing anomie and conflict in Israeli society.

One package for Biden, or was it right for Bibi not to give weapons to Ukraine

Now, in the information and political space, largely thanks to U.S. President Joe Biden, the Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the war between Israel and HAMAS are interconnected. This connection is seen from both financial and geopolitical perspectives. Competition for weapons and resources has become a reality for both Jerusalem and Kyiv.

Although, in terms of the dynamics of conflicts and their history, they seem diametrically opposed. The Ukrainian-Russian conflict evolved from peaceful cooperation after the dissolution of the USSR and a unified economic space to a war for survival. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict developed from a war for survival to Arab members in the Knesset coalition and the Abraham Accords with Muslim countries.

During the expert discussion on November 20th, the results of the reconnaissance interviews conducted by “Dor Moria” in late October and early November 2023, before the development of the mass sociological survey questionnaire, were considered. In the “Israel after the War” interviews, questions were also asked about parallels between the Russo-Ukrainian and Israeli-Palestinian conflicts. For example, the thesis “It was right for Netanyahu not to give weapons to Ukraine. There was nothing to defend themselves with at the time” is also connected to parallels between these conflicts.

According to the results of the “pre-war research” conducted by Dor Moria in April 2023, even then, the interest in the Russo-Ukrainian conflict among Hebrew-speaking Israelis was three times less than among Israelis from the former USSR territory. Now, for Hebrew-speaking Israelis, the war in Ukraine has become even less interesting than it was before October 7th.

However, as experts noted, the question of providing weapons to Ukraine may arise again after the war, especially considering the current dominance of the United States in Israel’s security matters.

Party and Religious Discrepancies

Our 2023 research indicates clear party and religious discrepancies on the issues we examined. For example, concerning the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, religious Jews and representatives of the right-wing political spectrum took a more anti-Ukrainian position than secular Israelis and supporters of left-wing parties. A similar division was observed regarding judicial reform.

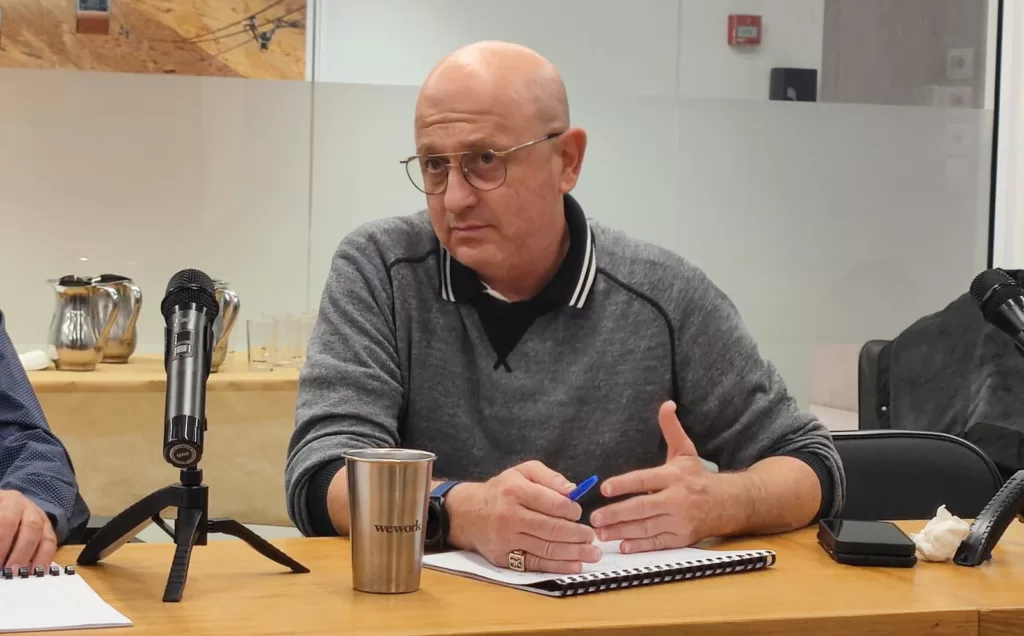

Regarding expectations for the U.S. elections, secular and Arabic-speaking Israelis preferred the victory of Democrats (43–45%, compared to 18–29% among varying degrees of religious Jews). Religious Jews predominantly favored the victory of Republicans (33–50%, compared to 8–24% among Arabs and secular Israelis).

Daniel Gricero – political strategist, expert in working with political movements and the media

These disagreements also manifested in the attitudes of Israelis toward the theme of ‘Israel after the war.’

Even on the question of whether it is possible to completely destroy HAMAS, the answers correlated with party affiliations.”

| Possible | Impossible | Total | |

| Political Orientation | |||

| Ultra-right | 85% | 15% | 100% |

| Moderately Right | 65% | 35% | 100% |

| Center | 59% | 41% | 100% |

| Moderately Left | 58% | 42% | 100% |

| Ultra-left | 100% | ||

| Country of Birth | |||

| Israel | 65% | 35% | 100% |

| Former USSR Countries | 69% | 31% | 100% |

| Others | 72% | 28% | 100% |

A similar correlation is evident regarding the question of the format for resolving the Palestinian issue.

Support for the concept of ‘Two States for Two Peoples’ is endorsed by representatives with moderate-left and left-leaning political views, with 67% and 69%, respectively, expressing their support.”

Representatives of the right and center-right, who more frequently support the idea of annexing the West Bank/territories of Judea and Samaria, as well as the Gaza Strip, garnered 70% of the votes in favor of this option.

The ‘Center,’ most concentrated around the ‘Two States for Two Peoples’ position, is supported by just over a third of the votes, and 33% of them found it difficult to answer.

Respondents born in the territory of the former USSR, like other citizens, somewhat more often endorse the ‘Two States for Two Peoples’ concept, and least of all, the ‘One State for Two Peoples’ idea.

Ethno-religiously, the greatest similarity is noted in the positions of secular Jews and Arabs, who express support for the ‘Two States for Two Peoples’ model far more frequently than other groups (42% and 40%, respectively, compared to 5–17% in other groups).

Jews adhering to tradition (30%), and even more so, the religious and ultra-religious (52%), significantly more often advocate for the annexation of the West Bank/territories of Judea and Samaria, as well as the Gaza Strip. Among secular Jews and Arabs, this position is supported by 6 to 18% of respondents.

Secular Jews and Israeli Arabs as a Unified Block

It should be noted that the trend of convergence between the positions of secular Jews and Arabs is also evident in our other research.

For instance, in responses regarding expectations from the U.S. presidential elections, religious Jews prefer the victory of Republicans (33–50% compared to 8–24% among Arabs and secular Israelis), while secular and Arabic-speaking Israelis prefer the victory of Democrats (43–45% compared to 18–29% among varying degrees of religious Jews).

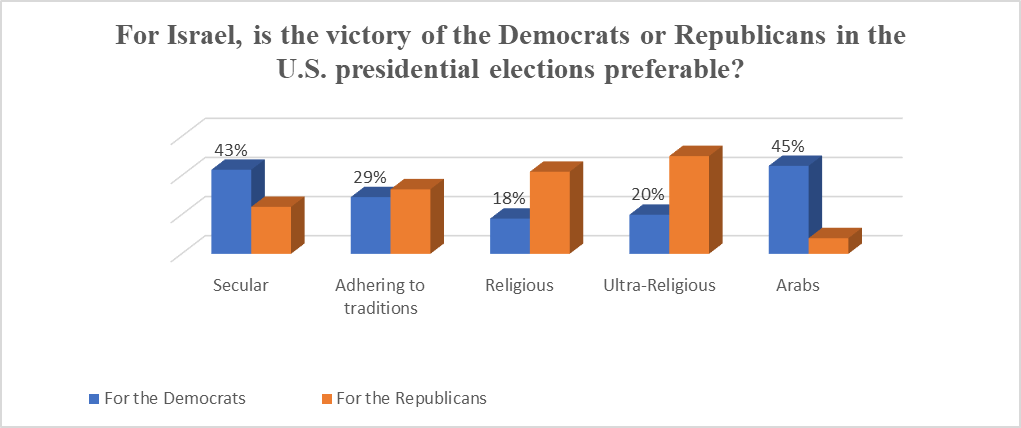

Only 16% of secular Jews and 14% of Israeli Arabs have complete trust in the judicial system, while among varying degrees of religious Jews, it is no more than 3%, a value within the margin of error of the sample.

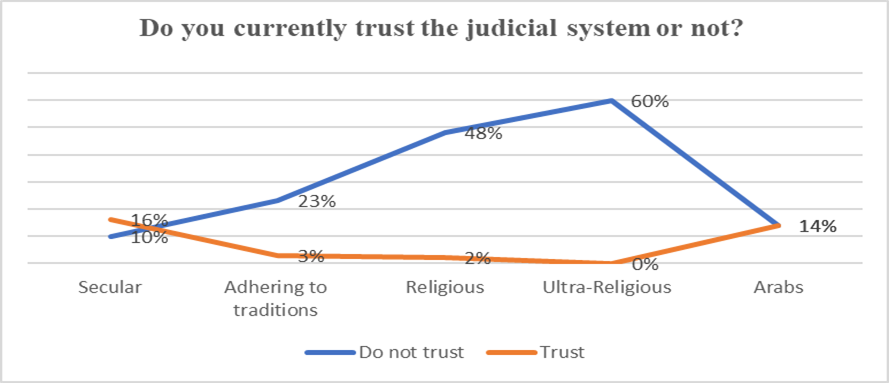

Among secular Jews and religious Arabs, responses characterizing protests as an effective tool for influencing politics are more common (63% and 46%, respectively), and less common among religious and ultra-religious Jews (16% and 25%). Conversely, religious and ultra-religious Jews are more likely to assert that protests harm society, destabilizing the situation (59% and 46%, compared to 14-15% of secular Jews and Israeli Arabs who share the same view).

Attitudes toward Israel after the war

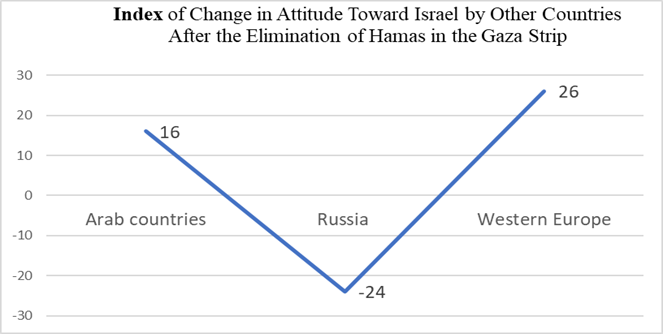

Israelis’ perceptions of changes in attitudes toward Israel after the war are of interest.

According to the opinion of a total of 42% of respondents after the elimination of the Hamas organization, relations with Arab countries will improve.

Positive expectations are also predominant regarding Western European countries: a total of 45% anticipate a possible improvement in their attitudes toward Israel, with 12% expecting a significant improvement.

In contrast, predictions regarding Russia’s attitude toward Israel are more negative. While a total of 13% of respondents express the possibility of improving these relations, 37% anticipate a deterioration.”

Among responses regarding the attitudes of other countries toward Israel, those characterizing positive expectations prevail. The highest values of the expectation index are related to the improvement of relations with Western Europe (+26), significantly lower but still positive, are associated with attitudes from Arab states (+16). The expectation index for relations with Russia is negative (-24).

The respondents born in the countries of the former USSR anticipate the most deterioration in relations with Israel from Russia, with a total of 44% against 30–37% in other groups. They are also somewhat less likely than others to speak about a possible improvement in relations (a total of 9% against 12–14% in other groups).

Russian Factor

From the perspective of attitudes toward Russia, it is interesting to observe the dynamics of changes in the opinions of Israelis regarding the possible risks of involving the State of Israel in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

| Risks | April 2023 | July 2023 | November 2023 |

| Conflict and damage to relations with Russia | 56% | 54% | 48% |

| Conflict and damage to relations with Ukraine | 3% | 4% | 2% |

| Conflict and damage to relations with the U.S. and other countries | 9% | 10% | 7% |

| Economic damage, reduction in foreign investments, and the like. | 5% | 8% | 5% |

| Damage to the stability of Israel’s national security | 5% | 3% | 5% |

| Damage to Israel’s national stability from a social perspective | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Damage to Jewish communities worldwide | 3% | 3% | 5% |

| No risks at all | 2% | 4% | 7% |

| Don’t know | 15% | 12% | 19% |

The conflict and damage to relations with Russia are the only risks that the respondents have been talking about for a long time. The decrease in the values of responses characterizing this risk in November is most likely due to Israel’s war in Gaza. There are no changes in response values among respondents differing by country of birth. Minor differences exist in responses based on political orientations.

Instead of conclusions: Is a sharp civil confrontation possible after the war?

During the expert meeting held on November 20, various opinions were expressed regarding the possible escalation of civil confrontation on the above-mentioned issues. To what extent will the theme of the “accelerated” resolution of the Palestinian issue, under the supervision of the United States and the Gulf monarchies, intensify civil confrontation? Will protests related to the continuation of judicial reform and the personality of Netanyahu and his ministers return? Will they intensify the general rift in society?

How will the mass distribution of weapons and the creation of militarized formations in various settlements, carried out by Ben Gvir, affect post-war stability? Especially in the settlement sector.

To what extent will the intelligence and army failures that led to numerous casualties on October 7 become a cause for a “search for enemies” and a shake-up in the political situation against the backdrop of “Palestinian state-building”?

Various experts note that after the sharp solidarity of society (including Israeli), several scenarios can be realized:

- Continuous support for the “patriotic fervor,” especially considering that Israel is turning into a “besieged fortress,” in light of the increased negative attitude towards the war from major geopolitical players and Israel’s partners.

- Transition to a state of the new normalcy, the “routine of war,” in which the state and society limit discussions and debates on pressing domestic issues and the “search for culprits” in the events of October 7th.

These two scenarios imply a prolonged war and a restructuring of the socio-economic system into a mobilization format.

In the event of a swift conclusion to the war, the scenarios may be more negative:

- Search for Enemies and Netanyahu’s Displacement: This would lead to a political crisis and potential re-elections in the Knesset. Experts note that only SHAS could afford to go for re-elections since its mandate count would remain unchanged. Other coalition parties might lose a significant number of their deputies.

- Even if Netanyahu remains, the U.S. will push Israel towards creating a Palestinian state, especially considering the upcoming U.S. Presidential elections. This could resurrect and significantly amplify accumulated disagreements. Since the question of creating a “Palestinian state” is viewed by many Israelis as a matter of Israel’s survival. It’s either Israel or the Palestinian state. Given the weak political center, it can be assumed that the party-religious divide will accompany discussions on the Palestinian state issue.

It is crucial to start engaging with public opinion and politicians now to mitigate the risks associated with internal discrepancies in Israeli society and heated discussions around the creation of a “Palestinian state.”